Jerry Seinfeld (the sitcom character, not the real-life dude) was a successful, semi-famous comedian who lived in Manhattan apartment that probably measured about 800 square feet.

By contrast, Monica Geller and Rachel Green were, respectively, (in Friends‘ first season) a chef and a coffee shop waitress who lived in an apartment about four times the size of Jerry’s.

Oh, and their place was always spotlessly clean and impeccably decorated, to boot.

And don’t get us started on how much free time they had to hang out with their pals!

We’re obviously not the first ones to observe that Friends offered an escapist, proudly unrealistic portrayal of life in one of America’s most expensive cities.

And to the show’s credit, like Sex and the City, it at least made occasional mention of the characters’ financial struggles.

But these brief allusions usually took the form of jokes, or one-off, single-episode storylines.

Neither series was interested in truly engaging with the grim realities of life under grinding poverty.

Of course, these shows are not alone in their lack of interest in money troubles.

Stories thrive on conflict, and the struggle to make ends meet is one that most viewers can relate to.

Scenes From the Class Struggle on Sitcoms

And yet, modern TV writers seem to have little interest in that nearly universal aspect of the human condition. But it wasn’t always that way.

We mention the difference between Jerry’s apartment and Monica and Rachel’s because the years when both shows aired simultaneously marked a transitional period that was rarely discussed at the time:

Though their respective runs on NBC overlapped by several years, Seinfeld and Friends were designed to appeal to different generations:

Seinfeld was a show by and primarily for baby boomers, a group who was, at that time, settling into middle age.

Friends, conversely, was written for bright-eyed, optimistic members of Gen X, many of whom looked at the characters as aspirational figures.

This, we could say, was the beginning of TV’s troubling attitude toward the struggles of the working class.

A Time of Plenty (At Least on TV)

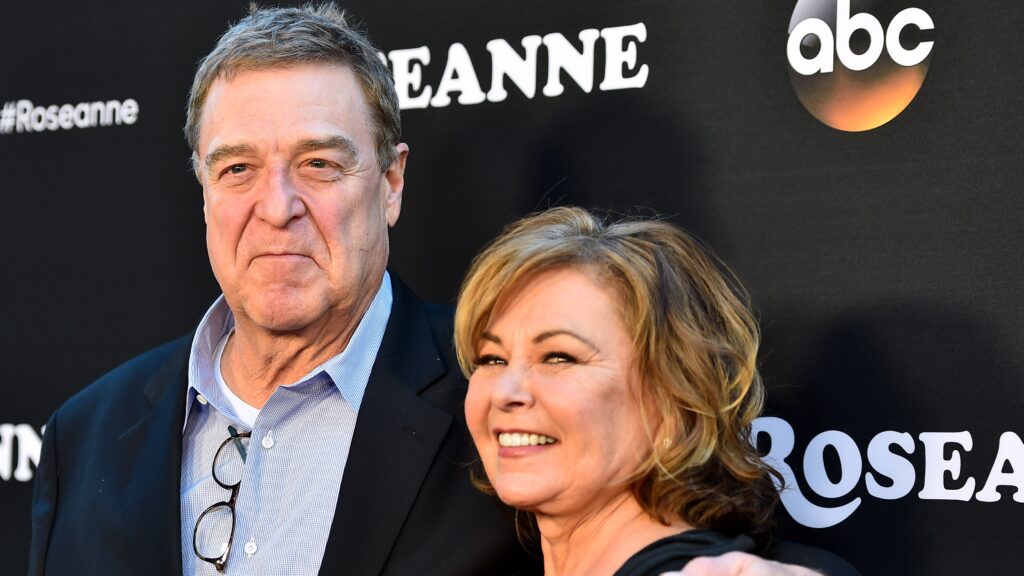

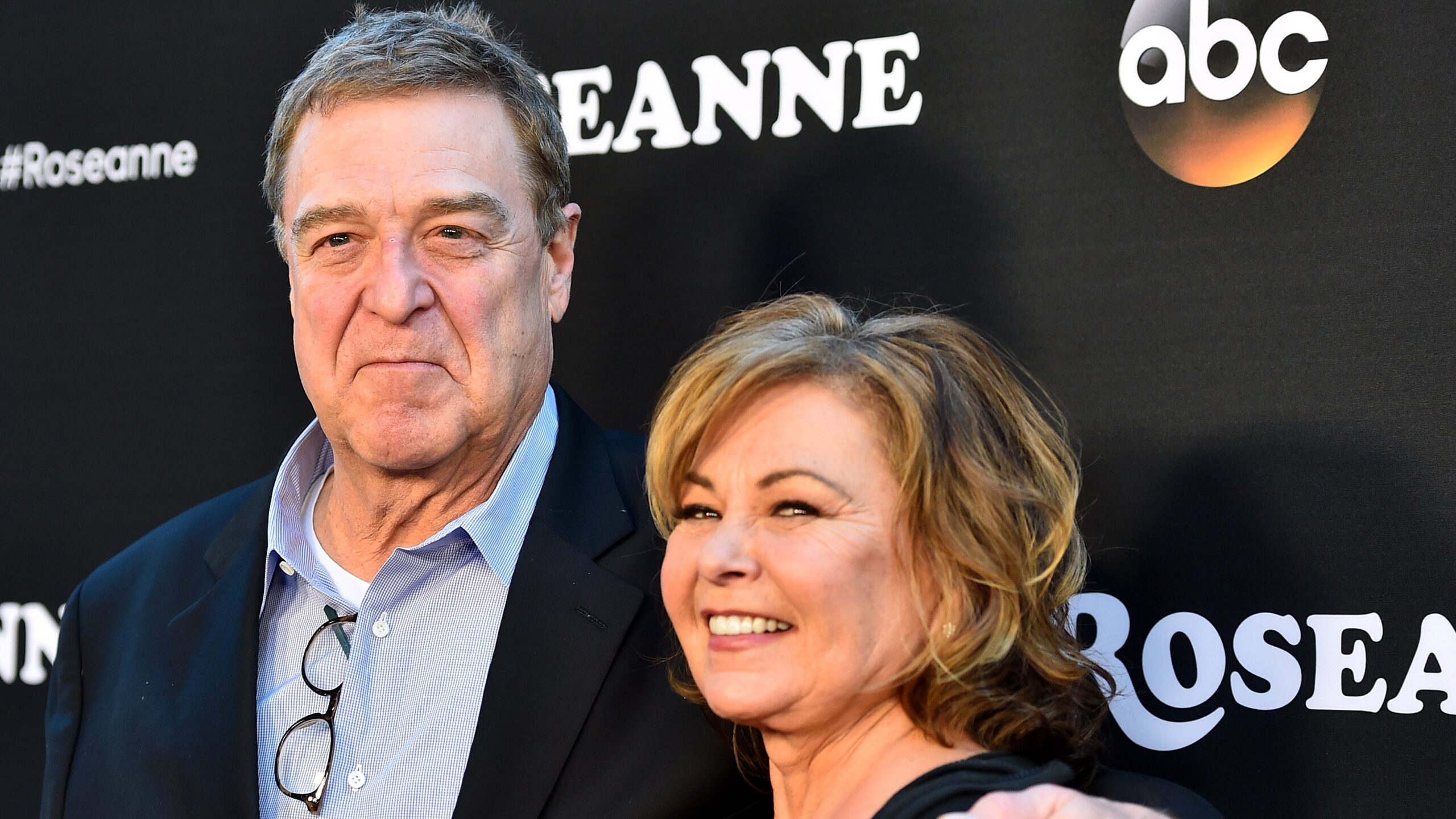

After decades of shows like All in the Family, Sanford and Son, and Roseanne, with the dawn of the 21st century, writers and networks seemed suddenly uninterested in the struggles of folks who find themselves clinging to the bottom rung of the economic ladder.

It’s no coincidence that the characters on Friends proved upwardly mobile beyond most people’s wildest dreams:

(Joey, for example, advanced from chronically unemployed aspiring actor to daytime soap star.)

Like sitcoms of the 1950s, the show was more interested in presenting an idealized version of the world than a believable one.

You could call it a step back for the genre, but it’s fine for some shows to take such an idealistic approach — the problem arises when every show chooses to conveniently sidestep real life.

And the problem’s not limited to sitcoms, either.

The Elites of the 10 pm Time Slot

The top dramas of the 2020s are almost all focused on doctors, lawyers, and cops who never seem to experience a single financial setback.

Think of a show like Fire Country, where at least half of the characters should be coping with financial constraints (firefighters and EMTs are, like teachers, sadly underpaid in this country).

And yet, we never see that side of their lives on screen.

The biggest drama of last season, CBS’ Tracker, had the potential to undermine this trend.

After all, Justin Hartley’s survivalist character is technically unemployed.

But it seems that the life of an itinerant reward-seeker is a surprisingly lucrative one.

So instead of presenting the hero as a Steinbeckian modern-day tramp, we get a living testament to the joys and advantages of the gig economy.

The Last Gasp of Socio-Economic Realism

Few recent dramas have made any real effort to depict the lives of Americans who do their best amid daily worries about making next month’s rent.

The handful series that demonstrated any interest in this segment of the population — like Showtime’s Shameless — presented the working poor as cartoonish, white-trash con artists and criminals.

To be fair, there are some shows that still reflect an interest in the struggles faced by most working Americas.

There’s the Roseanne spinoff The Conners, of course — though that show will soon come to an end with its seventh and final season.

And there’s Abbott Elementary, which — deals with the realities of trying to provide equal opportunities in a school beset by budgetary issues.

But such series are few and far between these days, which is a surprising development in an era and medium that’s otherwise reflecting a refreshing, newfound interest in representation.

As is usually the case with widespread cultural trends, there’s no single explanation for this phenomenon.

Generally, in situations like this one, network execs are simultaneously responding to the public’s tastes while shaping them at the same time.

You would think that in a time of record inflation and growing uncertainty about the future of the job market, Americans would embrace TV shows that portray their current woes in realistic fashion.

But maybe the opposite is true.

Perhaps after a day of stressing over the rising cost of living, the average viewer just wants to live vicariously through characters who have no such concerns.

And it’s not as if writers are ignoring economic matters entirely.

In fact, shows like Succession and Billions deserve credit for deftly threading the needle — offering commentary on the current state of American capitalism through searing portrayals of its victors.

In this way, they enable viewers to enjoy a bit of righteous indignation — a little smattering of class warfare — with their escapism.

Perhaps in the end, watching the relentless suffering of our nation’s impoverished classes is just too depressing for the average viewer.

But watching undeservedly rich people suffer? Well, that never gets old!

What do you think, TV fanatics? Do we need more socio-economic diversity on TV?

Hit the comments section below to share your thoughts!