Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com – Puck, also called Robin Goodfellow or “Hobgoblin,” is undoubtedly one of the most popular characters in English folklore.

Famous for mischievous pranks and practical jokes, Puck has captured the hearts of many people.

Left: Joseph Noel Paton, Puck, and Fairies, detail from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. – Right: Puck by Carl Andersson Midsommarkransen, Stockholm, Sweden. Credit: Boberger, Public Domain – CC BY-SA 3.0

One reason Puck has become so popular is that several authors and poets have included this playful character in their works.

Shakespeare’s Visit To The Magic Valley

The most famous Puck version can be encountered in William Shakespeare’s play A Midsummer Night’s Dream, based on this fascinating ancient figure. In Shakespeare’s play, Puck is a clever fairy master of harmless mischief. His benevolent pursuit of physical fun makes him adorable.

Of course, we like Puck in the play A Midsummer Night’s Dream because Shakespeare used his talent to create a magnificent world where fairies are primarily free from demonic qualities.

In Shakespeare’s play, Puck is the servant of the fairy King Oberon, who is angry with Titania, the fairy Queen. The king is jealous of the Queen’s Indian slave boy, and Puck is sent to acquire a magical flower.

When given to a sleeping person, the flower’s juice can make people fall in love. The Puck spreads the juice but on the wrong person. His mistake leads to people falling in love with the wrong people, which is not what King Oberon wished for.

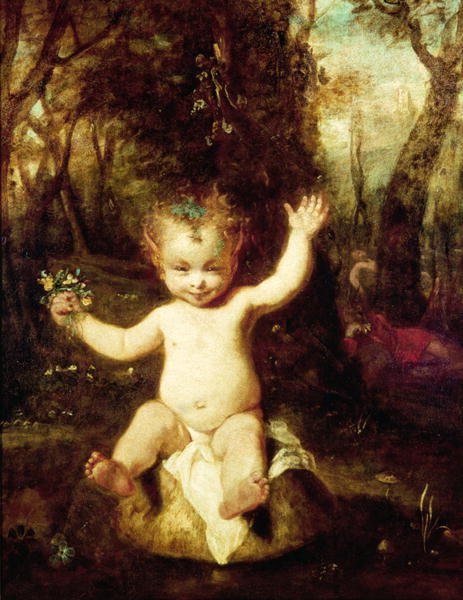

In Puck, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, for the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery, the once-dangerous figure is rendered harmless. Credit: Public Domain

Consequently, Puck must correct his mistake, which initiates a series of events.

This error correction sets in motion an adventurous sequence, leading to various developments and encounters. These actions amend his initial misstep but result in unexpected consequences and experiences for the characters involved.

“I am that merry wanderer of the night.

I jest to Oberon and make him smile,

When I, a fat and bean-fed horse, beguile,

Neighing in the likeness of a filly foal:

And sometimes lurk I in a gossip’s* bowl,

In the very likeness of a roasted crab,*

And when she drinks against her lips, I bob

And on her withered dewlap* pour the ale.

The wisest aunt, telling the saddest* tale,

Sometimes, for three-foot stool mistaketh me;

Then slip I from her bum, down topples she,

And “tailor*” cries and falls into a cough;

And then the whole quire* holds their hips and laughs,

And waxen* in their joy, and neeze,* and swear

A merrier hour was always well-spent there.

(A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2.1.43-57)

It is also quite interesting to learn how the great English writer William Shakespeare (1564- 1616) may have come up with the idea of giving Puck a significant role in one of his plays.

In his book Middle-Earth in Magic Mirror Maps, author Stephen Ponty writes that Shakespeare received his knowledge of the Cambrian fairies from his friend Richard Price, son of Sir John Price, of the convent of Brecon.

According to Ponty, “it is even claimed that Cwm Pwca, or Puck Valley, a part of the romantic glen of the Clydach, in Breconshire, is the original scene of the Midsummer Night’s Dream ‘–a fancy as light and airy as Puck himself. [According to a letter written by the poet Campbell to Mrs. Fletcher in 1833 and published in her Autobiography, it was thought Shakespeare went in person to see this magic valley. ‘It is no later than yesterday,’ wrote Campbell, ‘that I discovered a probability–almost near a certainty-that Shakespeare visited friends in the very town (Brecon in Wales) where Mrs. Siddons was born and that he there found in a neighboring glen, called “The Valley of Fairy Puck,” the principal machinery of his “Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

Illustration from the title page of Robin Goodfellow: His Mad Pranks and Merry Jests (1629). Credit: Public Domain

We need to find out how and why the great English poet gave Puck a significant role in his play. Maybe he had read about this curious folklore creature and liked it so much that he considered the figure worthy of becoming part of his play.

It should be added that the idea of Shakespeare visiting a magic valley is based on Welsh tradition.

Where Does The Name Puck Come From?

Where the name Puck comes from is still being determined. The modern English word is attested already in Old English as puca. Different types of tricksters frequently appear in myths and legends worldwide.

It has been suggested that Puck is of either Scandinavian, Celtic, or Germanic origin. Whatever the case, the figure has been part of English folklore for hundreds of years. The earliest reference to “Robin Goodfellow,” cited by the Oxford English Dictionary, is from 1531.

Modern scholars think the name can be traced to Ireland, pointing out that the word is widely distributed in Irish place names. Since Puck is a shape-shifter, he can quickly turn into, for example, a horse and bird, and in Ireland, he is known as Pooka, a mythical and not entirely benevolent prankster.

Puck Is A Lonely But Playful Trickster

Puck is a lonely figure who tries to get friends on many accounts. He can do minor housework for humans, and if you give him a small gift such as a glass of milk or other such treats, he can even work for you. Puck is not a selfish creature. At night, he sometimes does small services for the family he presides with. In Scotland, people know him as a brownie.

The Germans refer to him as Kobold or Knecht Ruprecht and in Scandinavian, he is called I Nissë God-dreng (Nisse god dräng)

Puck is popular among adults and children. Robin Goodfellow is simply a beloved mythological figure.

Written by Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com

First version of this article was published on June 24, 2021

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com and Ellen Lloyd

Expand for references